A couple weeks ago we here at MinionWare got into a very heated argument that lasted most of the morning and part of the afternoon. The argument was around the backup tuning settings in Minion Backup (MB), and how they should work vs. how they actually work.

The problem came about because Jen was doing some testing for her first MB session at a user group. She came across an issue with the tuning settings when she added the time component to the Minion.BackupTuningThresholds table. She noticed that she wasn’t getting the tuning settings she thought she should get when she was trying to tune for a specific time of day. So naturally she assumed I was stupid and filed it as a bug.

In actuality though it’s doing exactly what it’s supposed to, and it’s following the letter of the Minion Backup law. That law is “Once you’re at a level, you never go back up”. Let me show you what I mean.

Precedence in the Tuning Thresholds table

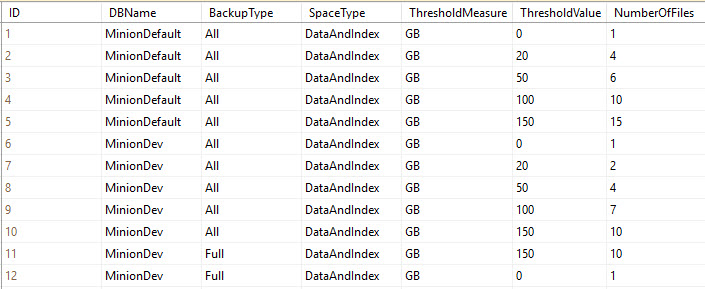

Take a look at this sample Minion.BackupTuningThresholds table.

Ok, in the above table we’ve got some tuning rows. This is a truncated version of the table, but it’s all we need to demonstrate precedence. We’ve got two rule sets here; one for MinionDefault (the row that provides all the default configuration settings), and one for MinionDev (a specific database on my server).

- MinionDefault is a global setting that says unless the DB has an override, it’ll take its rows from here.

- MinionDev is the only DB on this server that has an override, so it’ll take its settings from the MinionDev rows.

At the most basic level, the precedence rule states that once there is an override row for a database, that database will never leave that level…it will never default back to the default row. So in this example, MinionDev is at the database level for its settings, so it will never go back up to the more generic MinionDefault row. Once you’re at a level, you stay at that level.

A “Zero Row” for every level

I’m going to explain how these rows work, and why they are the way they are. Notice that for both levels (that is, for the MinionDefault rows, and for the MinionDev rows), there is what we call a zero row. This is where the ThresholdValue = 0. The zero row is especially important for the MinionDefault row, because this is what covers all DBs; it’s quite possible that you could get a database that’s less than your lowest threshold value.

In the above table, the lowest (nonzero) threshold value for MinionDefault is 20GB. That means that no DBs under 20GB will get any tuning values. Without any tuning values, the number of files would be NULL, and therefore you wouldn’t be able to backup anything…they wouldn’t have any files. So setting the zero row is essential.

And, since each DB stays at that level once it’s got an override, then whenever you put in a DB-level override it’s an excellent idea to give that DB a zero row as well. It may be 50GB now, but if you ever run an archive routine that drops it below your lowest threshold, then your backups will stop if you don’t have that zero row to catch it. Did I explain that well enough? Does it make sense?

That’s how the rule is applied at a high level between DBs. Let’s now look at how it’s applied within the DB itself.

“Zero Rows” within the database level

As I just stated above, you should really have a zero row for each database that has an override row (you know, where DBName = <yourDBname>).

Let’s look at MinionDev above. It has a BackupType=All set, and a BackupType=Full set. The All set takes care of all backup types that don’t have backup type overrides. So in this case, the All set takes care of Log and Diff backups, because there’s a specific override for Full. Get it? Good, let’s move on.

Notice that MinionDev has a zero row for the All set, and a zero row for the Full set. This is essential because following the rules of precedence, once it’s at the MinionDev/Full level, it doesn’t leave that level. So again, if there’s a chance that your database will fall below your lowest tuning threshold – in this case it’s 150GB – then the backup will fail, because there are no tuning parameters defined below 150GB. This again is why the zero row is so important: because it provides settings for all backups that fall below your lowest tuning setting.

And, if you were to put in a BackupType=Log override for MinionDev, it would also need to have a zero row. I could argue that it’s even more important there because it’s quite possible that your log could be below your tuning threshold.

So now, our Argument

That’s how the precedence actually works in the Minion.BackupTuningThresholds table. The argument started when Jen thought that it should move back up to the All set if a specific BackupType override falls below its tuning threshold. So in other words, in the above table, she wouldn’t require a zero row for the MinionDev-Full set. Instead, if the DB size fell below the 150GB threshold, she would move it backup to the MinionDev-All set, and take the lowest tuning threshold from there.

She said that it wasn’t in the spirit of the precedence rules to make the setting quite that pedantic. So after hours of arguing, drawing on the board, making our case, sketching out different scenarios, etc… we just kinda lost steam and moved on, because she had to get ready for her talk.

The point is though that this is the way it currently works: once it’s at its most specific level, it stays there. So, if you have tuning settings for specific backup types, you’d be really well served to have a zero row for each one just in case.

And I’ll also note that BackupType is the lowest granularity. So, Day and Time (another config option in this table) have nothing to do with this setting. You need to concentrate on the DBName and BackupType. Everything else will fall into place.

Final Caveat: We break the rule (a little)

Now, I know it sounds like a contradiction, but there is just one place where I break this rule. I call it the FailSafe. With the FailSafe, it’s possible to have specific overrides and still get your tuning thresholds from the MinionDefault zero row. Here’s why:

This is a rather nuanced config in Minion Backup, and it’s fairly easy to get something wrong and wind up without a backup. I didn’t want that to happen. So, if you do something like leave your zero row out for an override level, and your DB falls below your lowest threshold setting, you would wind up without any backup because there isn’t a number of files to pass to the statement generator.

Failsafe says, if you screw up and don’t have a tuning setting available, MB will grab settings from the MinionDefault Zero Row.

In this situation, I kick in the FailSafe mechanism, which pulls the tuning settings from the MinionDefault zero row. At least you’ll have a backup, even if it’s slow.

(That was one of Jen’s arguments: that a FailSafe is a great idea, but she wants it to come from the DB-All set instead of the MinionDefault-All set. I don’t know, maybe she’s right. Maybe that’s more intuitive. I’ll have to think about it. It wouldn’t be that big of a change really. I could walk up the chain. In the above table I could try the MinionDev-All zero row and if that doesn’t exist then I could use the MinionDefault-All zero row. What do you guys think?)

So why not just hardcode a single file into the routine so that when this happens you’re backing up to that single file? The answer is: flexibility. Your MinionDefault zero row may be set to 4 files because all your databases are kinda big and you don’t ever want to backup with fewer than that. So, set your MinionDefault zero row to something you want your smallest DB to use. If that’s a single file, then ok, but if it’s 4 or 6 files, then also ok. That’s why I didn’t hardcode a value into the FailSafe: It’s all about giving you the power to easily configure the routine to your environment.

Takeaways:

- The precedence rules are followed to the very letter of the law.

- Once a database is configured at a level, it stays there.

- The configuration level is specific to DBName, and then (at the next most specific level) to the DBName and BackupType.

- Whenever you have database-level override row, always have a zero row for it.

- Whenever you have a BackupType-level override, always have a zero row for it.

- The FailSafe defaults back to MinionDefault Zero Row, if a level-appropriate setting isn’t available.

Ok, that’s it for this time. I hope this explanation helps you understand the reasoning behind what we did.